11. Workshop skills

11.1. The Ballad of Jack Thompson

In the mid 1980s I met a remarkable scholar and artisan. Jack Thompson ran the Thompson Conservation Lab in Portland, Oregon [LienhardAConservationLab]. He developed techniques for the conservation of anything related to books, with a particular interest in medieval bookbinding technology.

Jack’s achievements were significant: he was the expert cited in all aspects of medieval book technology, from identifying types of ink, to how paper was made, to making sewing needles from hog bristles [ThompsonNeedles], and how to identify parchment [Thompson2002]. He also had designed and built the environmental system used to preserve the Lincoln Cathedral exemplar of the Magna Carta [Thompson1987], and taught an annual full-immersion workshop on “The Technology of the Medieval Book” in a remote off-the-grid mountain area in Idaho [Thompson1994].

I asked how he had reached his level of proficiency in both theory and practice, and he replied with a warm and gentle voice “For me it all started with workshop skills. I had always spent time in carpentry workshops […]”

Jack had then gone on to add a broad and deep knowledge of chemistry to his workshop skills. This combination of skills allowed him to carry out his wonderful conservation program.

This encounter was early in my career, and in my entire career I have noticed that:

Every area of endeavor includes a combination of theoretical knowledge and workshop skills.

Your achievement will be enhanced more by your workshop skills than by your knowledge of subject matter. You should spend your entire career perfecting and updating your workshop skills.

If you are a writer and a very slow typist, then you will not be able to get your idea down for revision and dissemination.

If you are a programmer then you spend a great amount of time moving chunks of text around within a file or between files. If you detach your fingers from the keyboard to use a mouse every time then you will be much less productive than someone who has mastered their programming editor.

If you are a cabinet maker and you have designed a wonderful piece of furniture, but you are not fast and precise with your table saw, then you will take a very long time to produce it, and you will not have a chance to implement your next design idea.

We will now look at various examples of workshop skills that are needed in most areas of scholarship.

Jack Thompson, 2002, “Identifying Parchment”, at: https://cool.culturalheritage.org/byform/mailing-lists/cdl/2002/0610.html

Jack Thompson, “Magna Carta in America : active environmental control within a display case for a travelling show”, in the IIC-CG GC annual conference, 1987. http://www.urbis-libnet.org/vufind/Record/ICCROM.ICCROM40271 – also referenced in https://cool.culturalheritage.org/waac/wn/wn09/wn09-3/wn09-309.html

Jack Thompson, “Workshop on the Medieval book”, 1994 – https://cool.culturalheritage.org/byform/mailing-lists/cdl/1994/0328.html

Jack Thompson, “Hog Bristle Needles” – https://web.archive.org/web/20180514032405/home.teleport.com/~tcl/f3.htm

John H. Lienhard, “A Conservation Lab” – https://uh.edu/engines//epi1051.htm

11.2. Keeping Research Tidy

Research is a process of accumulating many sources and perspectives on a subject. For this accumulation of information to really serve you, you need to be able to easily organize and access all of your sources. Any time you come across a new piece of information, regardless of how good you really think it is, you might want to see it again later. You need to develop some way of quickly keeping track of what you come across. This can be something as simple as a bibliography with citations in it, or a library created with database management software.

11.2.1. Citations

A citation is a short piece of text that contains information about where a source can be found. It’ll have information like the source’s title, its author(s), and its publication date. Storing citations for what sources you use helps you find those sources again later, and adding citations to the products you create lets people know who research and knowledge should be attributed to. Read more about the importance of citing sources in products in What is Plagiarism?

It can be daunting when you see the massive list of traits a citation needs, but you don’t always have to fill in every piece of information. Fill in all the information you have access to, but if you don’t have the publisher location, your citation will be okay without it.

Different teachers, professors, and fields will use different citation styles, here’s a very brief overview of the commonly used styles with their respective field.

Modern Language Association (MLA): often used in the humanities.

Author Last, First MI. “Source Title.” Container Title, Other contributors, Version, Number, Publisher, Publication date, Location.

American Psychological Association (APA): often used in the social sciences.

Author Last, FI. (Publication Date). Source Title. Publisher

Chicago Manual of Style (CMS): used in both the humanities and the sciences, depending on the variation, the notes and bibliography system or the author-date system.

Chicago uses two main citation styles, long note:

Author full name, Book Title: Subtitle, edition. (Place of publication: Publisher, Year), page numbers, URL.

And short note:

Author last name, Shortened Book Title, page number(s).

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): often used in engineering and computer science.

Author initials. Last name, Book Title. City (and state if in US), Country: Publisher, Year.

American Medical Association (AMA): often used in medicine and biological sciences.

Author last name Initials. Source title. Container. Year;Volume(Issue):Page range. DOI or URL.

Council of Science Editors (CSE): often used in the natural and physical sciences.

Author(s). Title. Edition. Place of publication: publisher; date. Extent. Notes.

Some other workshop skills often include a technological element, as typing with the writer mentioned before shows, sometimes in pursuit of greater challenges more sophisticated tools are needed. These technologies might look physical, like a planner, digital, like a source management software, or mental, such as understanding work style. Some of these may take getting used to, but they are rewarding tools to be respected and mastered.

11.2.2. Source Management Software

There are many pieces of software for managing your sources, and the one we’ll be talking about here is called Zotero. It’s free, open source, and cross-platform, but other solutions do exist. Below we’ll be walking through some of Zotero’s features and how to integrate it into your workflow.

To install Zotero, you’ll want to go to their download page. You’ll want to download both the desktop application for your operating system as well as the “connector” extension for your browser.

11.2.3. Adding Sources

11.2.3.1. Automatically With the Connector

First make sure that the Zotero desktop application is running. In your browser, navigate to the source you are using. This can be a news article, social media post, academic journal. The Zotero connector is really quite robust. In the toolbar of your browser, find the Zotero connector icon and click it. You should find a matching entry has been made in your desktop application’s library. If there is an associated pdf like with an academic journal, Zotero will automatically download it for you so you always have access to it.

Figure 11.2.3.1 The Zotero connector extension might not always be in the same place depending on your browser, but it’s most likely in the top right hand corner.

11.2.3.2. Manually in the Desktop Application

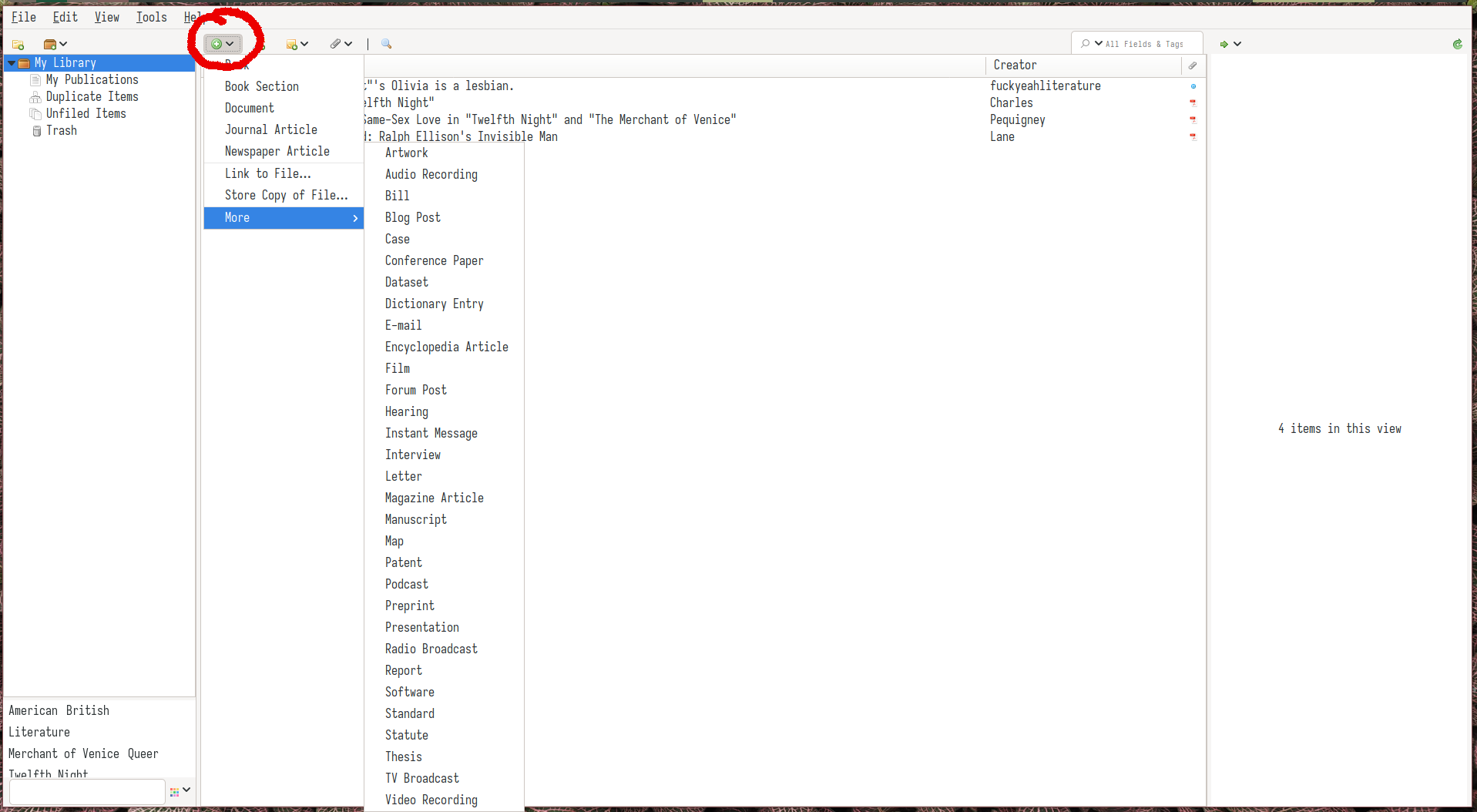

If for some reason the connector isn’t working, or if you’re working with a source not in your internet browser, you can add sources manually as well. In the top left is an icon that has a green circle with a white cross.

Clicking this will open a dropdown menu that lets you select the type of source you’re storing. Then a sidebar will let you input all of the fields that you have access to.

11.2.4. Annotating Sources

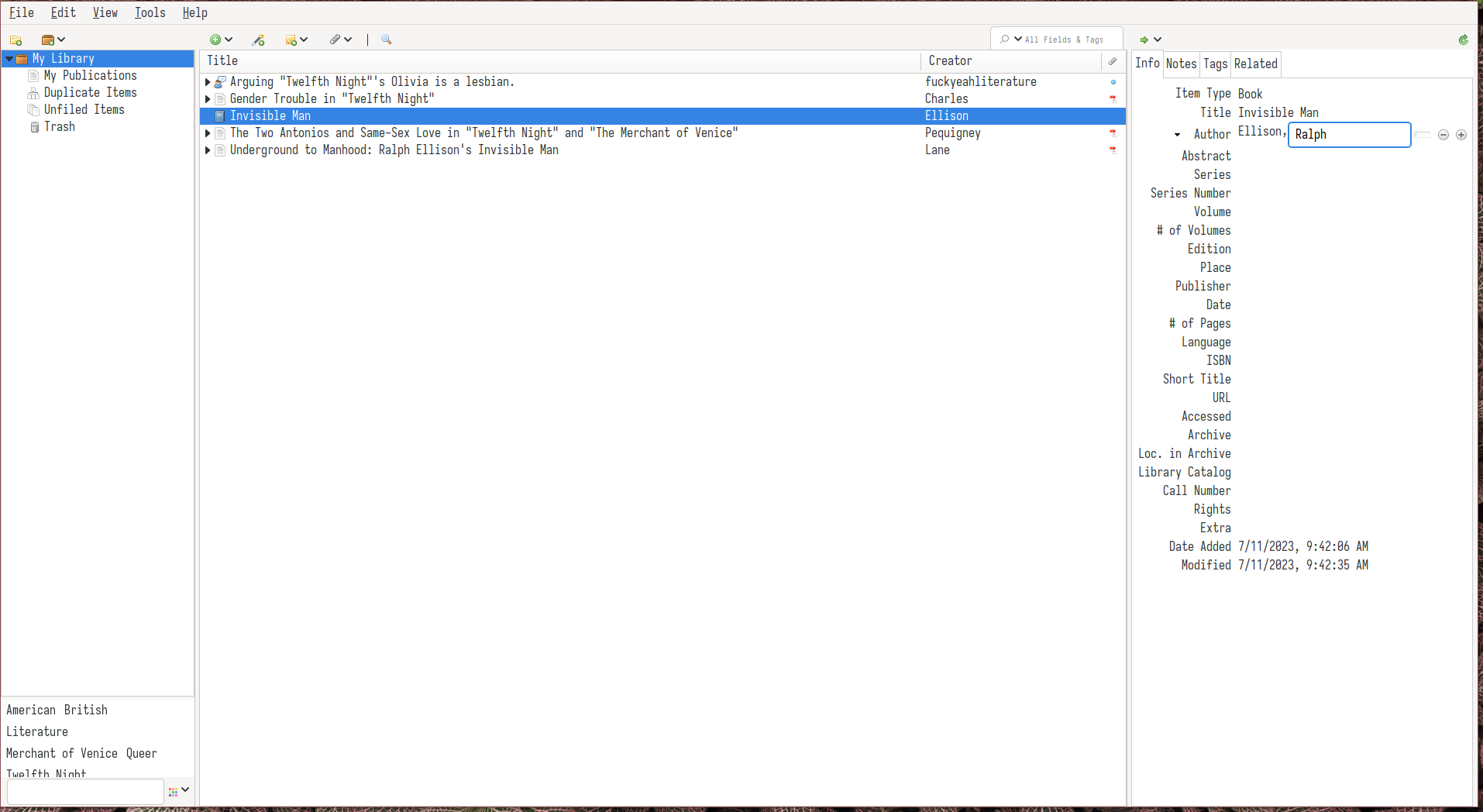

At the top of the sidebar where you manual add information about your source, there are a few extra tabs. Two important ones are “Notes” and “Tags”

Notes lets you add small pieces of formatted text to your entry for that source. These can be a great place to store information about what you thought about your source, what you might use it for. You can even use this as your primary note taking tool so that all of the information you have for your research is managed in the same place.

Tags let you organize your library so that it’s easier to find what you’re looking for later. If you have a bunch of sources on astrophysics and a handful of them are on pulsars, you could tag all of them with “pulsars” so that when you decide that you want to reference those sources again for a write up or presentation, you can see all of your pulsar related sources by clicking the “pulsars” tag that was created in the bottom left hand corner.

11.3. Time management

When balancing many due dates and topics, time management is a skill you must develop, and the sooner the better. Like most things, there is no one right way to time manage, but taking the time to find what works best for you can be easy, and will be worth it. Here are a few techniques I like to use when managing my time.

11.3.1. Planners

There are a multitude of types of planners on the market. There are daily views, weekly views, and monthly views. I suggest finding one with all three. There are some really fancy ones and some more bare bones ones on the market. Some programs available.

These three views are helpful for different reasons. The monthly view is useful when keeping track of upcoming deadlines, for example, a paper due or a test coming up. Something that you know about in advance and need to do some prep work for.

Weekly views are helpful for keeping track of short term deadlines, things like quizes or meetings. Having these short term appointments visible when your planning your week will help you more accurately guage what you can realisitically accomplish each day and week.

Daily views are great for day to day tasks. Making to do lists here will help you keep track of what you’d like to do each day, and over the long term will give you a good idea of how much you realisitically accomplish each day. Plus, it’s always fun to cross things off your to do list.

11.3.2. Knowing Your Work Style

Are you someone who can sit down and work for four hours straight? Or are you someone who works in short bursts. There is no perfect work flow, and trying to force yourself to work a certain kind of way will most like be unsuccessful. This is why it’s important to work with your brain, rather than against it.

If you find yourself loosing focus, try the Pomodoro method (working for 25 minutes, then a 5 minute break and repeat). Maybe some days will be better than others. If you feel stuck, try walking around the room or saying what the issue is outloud.

The environment you work in can greatly impact your flow. Are you someone who needs total silence, or are you someone who needs background noise. Do you like working around or with others? Or are you more of a solo worker?

Finding what style works best for you is a matter of trial and error, and it might even differ subject to subject, task to task. Finding your work style is important for time management because it allows you to be as efficient as possible.

11.4. Communication and Collaboration

11.4.1. Collaboration with peers

11.4.1.1. Clear Communication

Clearly communicating is an esstiential skill in all aspects of life, but especially useful when collaborating. When working with peers, clear communication looks like providing constructive feedback and being open to suggestions. The whole point of collaborating is the free exchange of ideas. If your peer has a suggestion for your work, or vice versa, keeping an open mind and friendly disposition will encourage a mutual exchange, and will result in a better end product than you might have been able to create on your own.

11.4.1.3. Assign and Delegate

Once the shared goal has been set, you can assign and delegate tasks. There is power in numbers, the more eyes on a project the more insight will be provided and the team will be more efficient. Build off skills and strengths of your team members. Is one person very organized? Is someone else well versed in tech? Not only will this allow each member to shine as individuals, but it will make it a smoother and well rounded process.

11.4.1.4. Respect and Trust

Respect diverse perspectives, foster trust and mutual respect, and be flexible. Doing these three things help create a supportive and positive environment. Teams where people feel unwelcomed or ostracized rarely do good work.

11.4.1.5. Resolving Conflict

Be ready to compromise, not everyone will agree all the time. It’s a cliche, but there really is no “I” in team. That being said, make sure you are advocating for yourself when appropriate. The best way to resolve conflict is an open discussion with the parties involved as well as other memebers of the team. Having a mediator present allows you to find a solution that satisfies all parties.

11.4.2. Collaboration with mentors

11.4.2.1. Communicate

Your mentor is there to help you, seek guidance and feedback. However, you don’t want to only talk to them when you have a problem. Even though they are there to help you, they are people too. Establishing regular communication, expressing gratitude, and staying connected will help you form a rewarding and long term relationship with incredibly interesting people! Just as you would when collaborating with peers, be receptive to guidance. That’s what they’re best at after all.

11.4.2.2. Respect

Your mentor has worked hard to get to their level of expertise in their field. It’s of the utmost importance that you show them respect. The easiest way to do this is by being respectful of their time. Not all mentors are the same, some will love to chat and be available anytime, others might not. Show them respect by maintaining confidentiality and trust, they are sharing their vast knowledge and forming a relationship with you, so it’s important to show appreciation for that.

11.4.2.3. Take the Wheel

Your mentors are more than likely very busy working on exciting new projects or lecturing other students. The best thing you can do it not make them do all the work for you. Establish clear goals and expectations, be proactive and prepared, take ownership of your growth. They are there to guide you, but if you don’t man the ship, nothing will come of it.

11.4.3. Effective use of email

Here is an example of an exchange between a student and one of his mentors.

The backdrop is that Dan had interned with Felix the previous summer, and had also been mentored by Jake in the past. Dan is a very good mathematician and programmer, but is still working on improving his written communication skills.

Now (spring 2021) Dan has called Jake to ask about summer job strategies, and that kicks off this sequence of emails.

Happy ending spoiler: after this exchange Dan got a summer job working for Felix.

Note

The people mentioned here are not called Dan Chesterton and Jake Clovelli and Felix O’Sullivan, but apart from changing their names, the exchange is reported here exactly as it happened.

- First request by student

From: Dan Chesterton <[email protected]> To: Jake Clovelli <[email protected]> Subject: email consulting Hey, this is Dan Chesterton, last night on the phone you said that you would review an email to Felix O'Sullivan and give me tips. Here is what I have at the moment " Hello, this is Dan Chesterton, you were my mentor last summer for the Computing in Research program. I was wondering if there was any work that I could do for you this summer, or if you knew of a place where I could do some computer-related work over the summer. "

- First response-by mentor

From: Jake Clovelli <[email protected]> To: Dan Chesterton <[email protected]> Subject: Re: email consulting Dear Dan, Here is a lesson in "soft skills". First of all, you use standard politeness tips. So for example, when you write to me you do not put it as a demand that I fulfill my promise, but rather as a "thank you". That means that this phrase: > Hey, this is Dan Chesterton, last night on the phone you said that you > would review an email to Felix O'Sullivan and give me tips. would have sounded much better to me if it had been: """Dear Jake, thank you again for offering to help review my email to Felix. Here is a draft -- do you think it could do with improvements?""" Do you see the difference? The wording I propose is introduced in a polite format which is standard for business correspondence. It goes on to show appreciation, and then asks for the favor within that spirit of thankfulness. As for the letter to Felix, here are some things to think about: 1. He certainly remembers you, so that beginning is awkward. 2. You need to show appreciation for what he did for you last summer. I don't know if you have written since then to say "thank you", but in any case you need to begin this letter in that way. 3. You do not mention how much you like systems programming and low level work. Your enthusiasm is what will make him happy and motivate him to look for something for you. Your phrasing sounds like "I need to make some money; can you help me do that". Instead it should be bursting with this kind of message: "last summer you showed me a fascinating path, through free and open-source software, to do technically really cool things. I would like to do more Linux work. Might you, or any people you know, be looking for summer interns to do IT or systems work?" 4. You do not mention what you've done since. He volunteered his time to work with you last summer. You owe him to keep him posted. (Side-note: you also owe it to Ms. Vilnius -- she did a lot of work to get you the job last summer.) If you understand those points, you could write me another draft. Then we can get into specifics.

- Next iteration from student

From: Dan Chesterton <[email protected]> To: Jake Clovelli <[email protected]> Subject: Re: email consulting alright, thanks for the advice, communicating with people can be a little difficult for me. here is what I have with your suggestions " Hello, I want to thank you again for helping me out with my project last summer. Since then I got accepted into NMT where I will double major in both Math and Computer Science, I have also been studying Java and abstract Math in preparation. Last summer you showed me the tip of what can be done with open-source software and the cool systems that you can make with it. I would like to continue to see the things that are being done with Linux and OpenWrt. I was wondering if you, or if you know of anyone, that is currently looking for interns to do IT or other related work. "

- Final tip from mentor

From: Jake Clovelli <[email protected]> To: Dan Chesterton <[email protected]> Subject: Re: email consulting > alright, thanks for the advice, communicating with people can be a little > difficult for me. Nah: once you make it a goal then it's a skill like any other, and your rewrite of the email is very good, so clearly it's just a matter of wanting to do it :-) The only thing I would suggest is that you add the two words "this summer" at the very end of the message, and then send it off.

- Closing of the exchange from student

From: Dan Chesterton <[email protected]> To: Jake Clovelli <[email protected]> Subject: Re: email consulting and the email is sent, thank you so much Jake!

11.4.4. A good start is not enough

Two years later there was a sad afternote to the story:

Jake recently met Felix and found out that in the end the student Dan had interned but never did any work. He just spent all his time scrolling things on his phone instead of taking initiative.

Conclusion? The better use of email worked well for Dan, but he still had to develop a more mature work ethic.